From a village in Dehradun, India to a wealthy White neighborhood in Phoenix, Arizona, Mom could not have fathomed who I would choose as my childhood ‘best friends.’ She would come home almost daily to a member of my friend group raiding our kitchen, which she diligently kept stocked with different flavored Izzes and miniature Ben and Jerry’s ice cream cups. I gave out our garage code like my Snapchat handle, and our home became a haven of sorts. Mom would drive us in her minivan anywhere we wanted to go at almost any time of day. Everyone’s parents trusted her to keep us safe.

My friend group in high school was comprised of four girls and three boys; two girls and all three boys were white, while myself and another girl were of color. I had the thickest hair, the darkest skin, and looked like absolutely no one around me. I was an anxious, depressed, and suicidal kid, with a 4.0 GPA and obsession with procedural crime dramas. I spent most of my time sobbing horizontally, while Mom watched from 5 feet outside my door. Most days, Mom ate dinner by herself in the kitchen, while I lulled myself to sleep with hours of internet and blue light. I could always hear her silverware scraping her plate, cutting through the silence of our mostly empty home. It sounded like loneliness; an immigrant parent adrift.

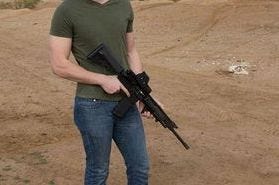

In between episodes of Law and Order: SVU, I would scroll through Facebook and interact with my friends. When they would replace their profile picture or write on my wall, I was the first one to throw it a ‘Like’ or a ‘Comment’. One day, the boys in my friend group started posting the inevitable.

I have no sense memory of my emotions while seeing these images. I know for certain I was not at all startled. I remember liking and commenting on each one. These three boys met through me, and my girl friends seemed to worship them. As baffling as it sounds, I did not equate the gun culture with violence. In my neck of the woods, guns were a ‘hobby’ and a reward. Photos with guns on social media were a form of power currency. Eventually, pictures of hand guns turned into pictures of machine guns, which these boys held with charismatic smiles on their faces.

Two of the three boys were more enthusiastic about guns than the third. The third musketeer was the token liberal of their group, though he mostly silently enabled the other boys’ behavior. My family life was deteriorating simultaneously, and I clung to my friend group with an unshakeable grip. During a developmental period of individuation and identity development, these boys solidified for me what ‘good men’ should look like. They were somehow superior in my adolescent brain to the droves of litigious, perverted Indian men I had spent my life calling ‘Uncle.’ I called the boys family. I called them brothers.

The budding therapist in me was always especially talented at helping my peers feel safe enough to share their vulnerabilities. These boys were no different, and I know they loved me for it. They would show me this love by giving me car rides to school, writing me a birthday letter telling me how special I was, and claiming me as their best friend in the Valentine’s Day ‘shout-out’ edition of our high school magazine. They would pick me up while I was crying in a corner of my neighborhood and take me for donuts. They trusted me for romantic advice, to take them shopping, and most notably, to keep their secrets.

After the love notes and happy times came their exclusion of me on boys’ night, fights about whether it was okay for them to yell the n-word, and hours of helping them with their homework. I wrote the supplemental essays of one of their college applications, earning them a seat at an Ivy League. Meanwhile, I refused to apply to top schools because I genuinely did not believe I would be accepted. I watched as they were emotionally merciless to everyone around them, performing the young men they thought they should be. If I paid close enough attention, I got glimpses of where they truly were in their capacity. Primitive understanding, weaponized incompetence, and brute emotional force.

One of the boys tried to ask out one of the girls in our group, and she was immediately ostracized. The boy in question sat silently while the other girls in the group teased her mercilessly for being ‘boy crazy,’ and a ‘slut,’ led by none other than the other girl of color. Instances like this duplicated, and mutated. The boys grew in their social power, and left us in the dust. Still holding their guns, still smiling. Never once pulling the trigger in a crowded room.

With patients, I often reference a sociopolitical theory known as The Overton Window. The Overton Window refers to the range of what the collective deems ethically acceptable in governance. When extreme governance occurs, the more the window of what is acceptable becomes polarized. Using less jargon, this process is akin to building an emotional callous to sharp pain. The bar stoops so low, it finds itself in hell, creating acute sensations our body experiences through dulled aches. The bare minimum of respect becomes a rare treat. I find it helpful to use the analogy of unknowingly drifting down shore in the ocean. You have no clue how you got there, and the tides were so strong, you could not have avoided it if you tried. Unless you just never got in the water.

Interestingly enough, my friendships with the three boys were the only ones in the group which lasted. Despite my integrity, my values, my critical thinking, and my work, my psyche found a way to compartmentalize the ugliness within them. This ugliness only grew in them with age, turning each of them into their own Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The behavior began to seep into all of their relationships, while their performance and truth grew farther apart. They would beg their partners to stay committed to them, then talk to folks on dating apps in the same breath. They would purchase a home in another state to self-sabotage a relationship in which they were unfulfilled. They would wax poetic about their ethics, then have a frighteningly violent interaction when discovering mice in their kitchen — stomping on them barefoot, drowning them in Tupperware, and hitting them with a 2x4. They would point out women in public they deemed ‘fat,’ and mock how their clothing looked on their bodies. They would make fun of each other for becoming intimate with ‘subpar’ partners, including one who was blind. They would tell stories of their fraternity brothers referring to a conquest as Moby Dick, and the ‘conquerer’ as Captain Ahab (an incorrect reference, might I add). They would mock my career choice, because “racism is not real,” “the gender pay gap is a myth,” “the police don’t kill that many black people,” “the government should not acknowledge 80 different genders,” and it was all a “giant pity party.” They remained uncurious about violence I experienced at the hands of an ex partner, even when it occurred under their same roof, in the next bedroom.

Any reaction I had was deemed sensitive. “Saira, why am I in the doghouse now?” “Saira, don’t be a b*tch.” “Saira, you’re just really sensitive.” Their families and our friends would stand by silently, refusing to name the behavior as aberrant. Apparently, these instances were popular and sensible within their Overton Window. Their parents still make horrific jokes using slurs like this one, model poor hygiene, and worship at the altar of Tucker Carlson. The systems into which these boys were born protected them from natural consequences to the point they became emotionally abusive and bereft. At this juncture, I had to give all three stooges a piece of my mind, and send two of them bell hooks for good measure. The third made me too f*cking mad. Whatever. Google is free.

As we collectively mourn yet another mass shooting in the US, I could not help but reflect back on these images and interactions. I shared them with my mom for the first time, to her shock and disgust. She never knew these boys who she watched grow up were hugging her with the same hands in which they held a lethal weapon for sport. She was unaware their emotional and relational violence could even exist, let alone invisibly scar me for life. She then shared with me her reasons for always keeping us under her roof, or in her car. When she emigrated, Mom knew Americans were gun owners. Sending me to their homes was roulette, because she also knew there was no way to safely ask American parents whether guns would be accessible to me. As long as she had her eyes on me, she could keep me safe. So she thought.

So she thought.